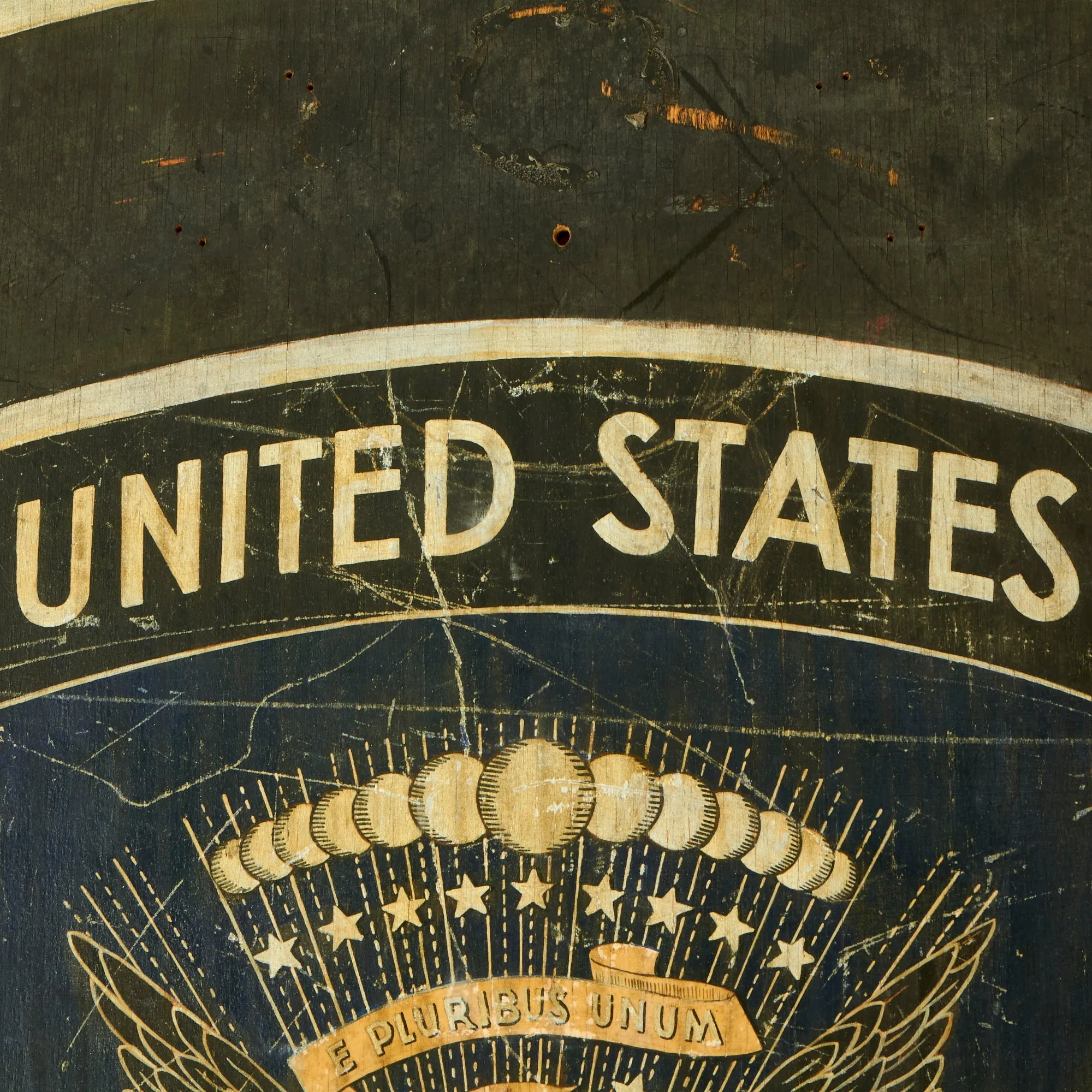

Original Item: Only One Available. This is a lovely example of a wooden “shield” bearing the Great Seal of the United States, also referred to as the “Coat of Arms”. This sign was once displayed in/on the US Embassy in Petrograd (present day St Petersburg) before closing in response to Bolshevik actions in 1918/19 during the Russian Civil War.

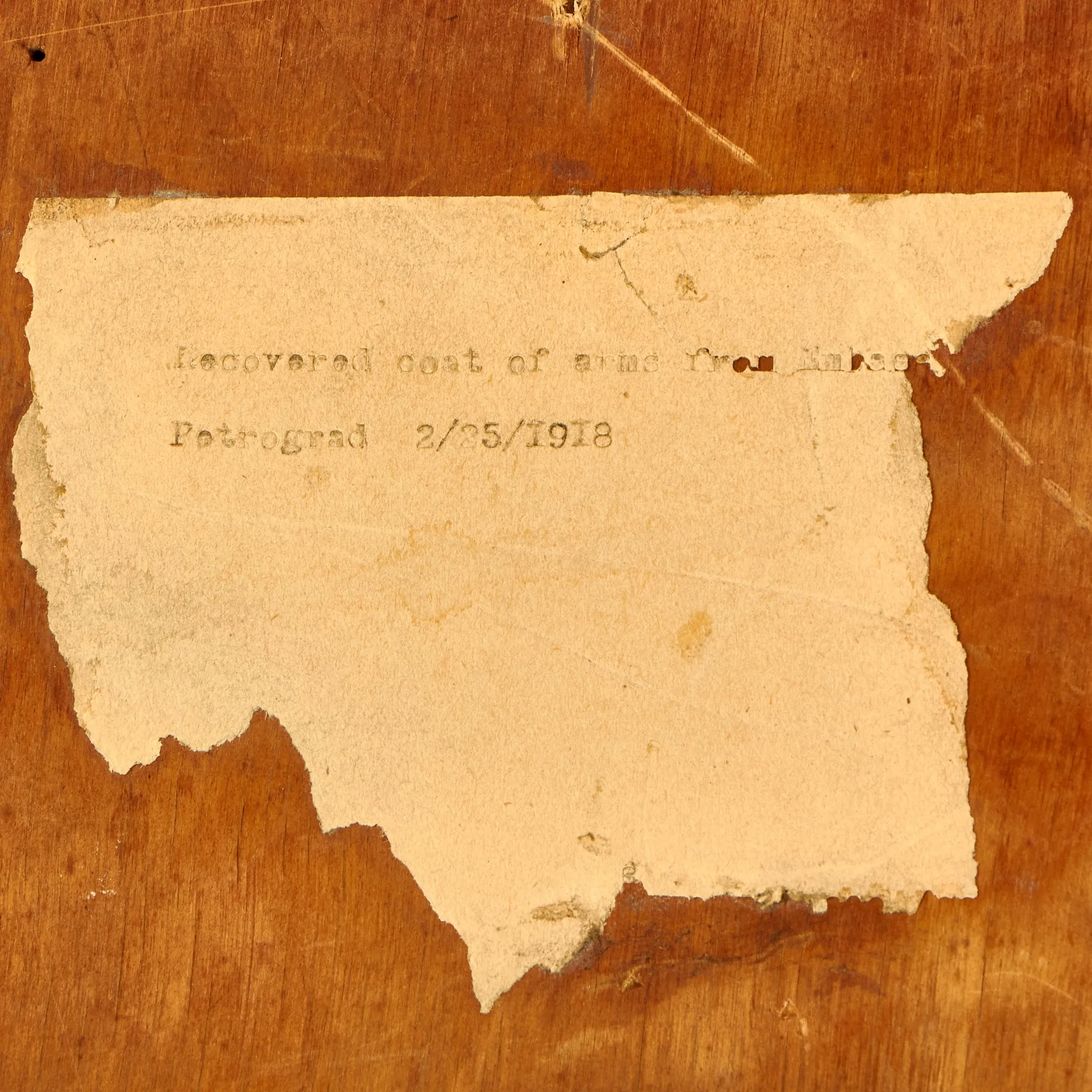

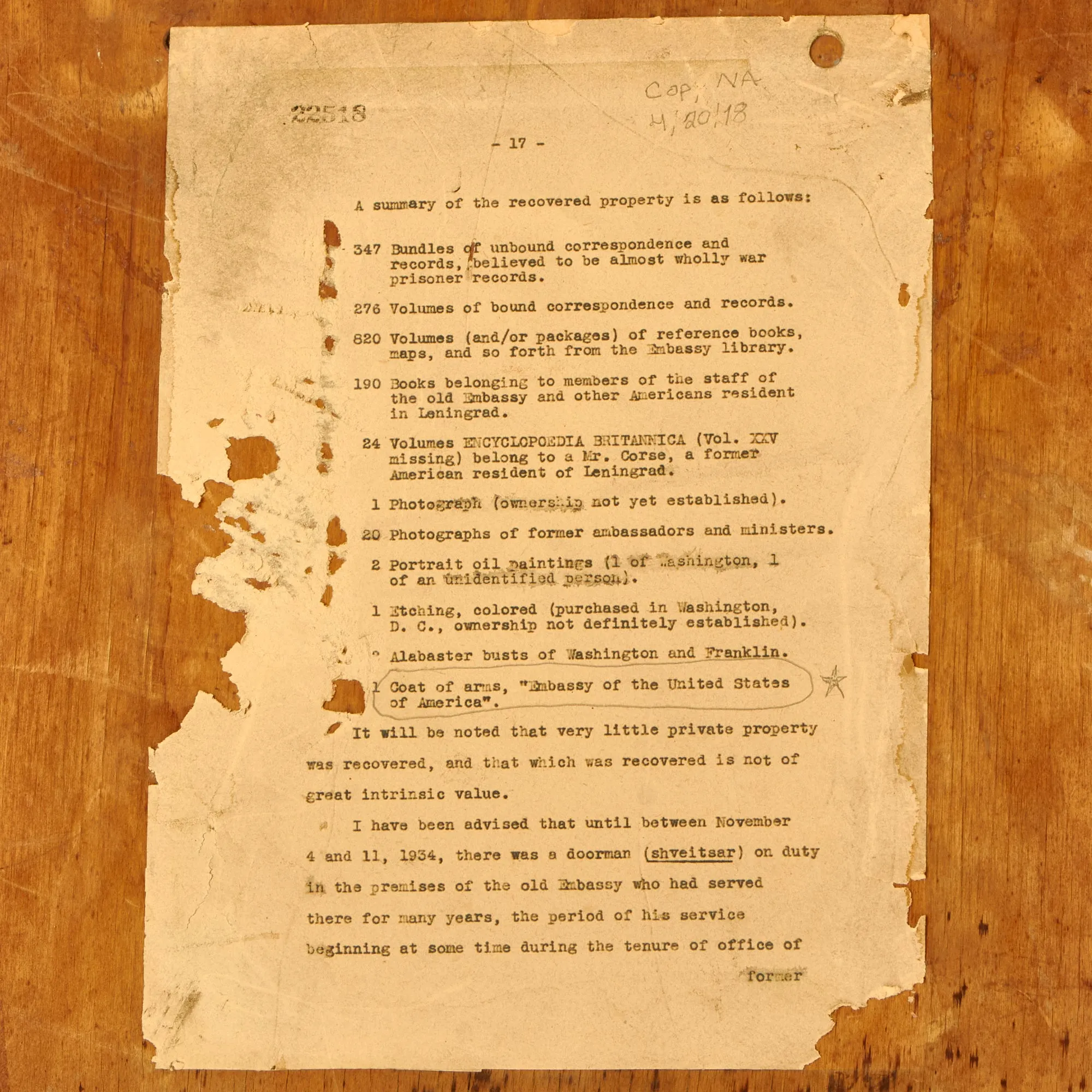

This 27” x 22 ½” painted wood sign is in wonderful condition with nearly all details present. The wood itself is in wonderful condition with the painted portions now cracked due to age and exposure to the elements. There is no significant damage present and the reverse side has some information pertaining to the items recovered at the U.S. embassy in Petrograd, listed on the sheet is this Coat of Arms as well as a 1918 date.

After some research, we were able to locate information about the embassy, but more importantly we found out who recovered the items and when, Angus I. Ward in 1934, which is interesting as he was not stationed there during this time. Ward (1893-1969) served in the U.S. Army during World War I and then became U.S. Vice Consul in Mukden, China, in 1926; then in Tientsin in 1927-29 and again in 1932. He was sent to Moscow in 1938, and served as U.S. Consul General in Vladivostok during WWII, in 1943. Before becoming U.S. Ambassador in Afghanistan in 1952-56, he was back in Mukden as Consul in 1948, where he became the subject of the Ward Incident (1948-49). During the final years of the Chinese Civil War, Ward and the consulate staff were imprisoned and held under house arrest by Mao Zedong's People's Liberation Army for almost a year, creating a diplomatic rift with the United States.

On July 4, 1934, Ward made the first of several trips to Leningrad (formerly St. Petersburg/Petrograd). During a visit on November 4, he called on Grigori Weinstein, the Leningrad agent of the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs, and requested permission to visit the old embassy building. Weinstein rebuffed him with the assurance that a search had been made previously and that nothing had been found because all the records had disappeared during the revolutionary period. As Weinstein said, "It is useless to go there Mr. Ward. Seventeen years! Revolutionary days, you know what happens in time of revolution."

Ward, however, knew better. He had information from three sources in Leningrad that the archives still existed. He persisted in his desire to visit the old building and informed Weinstein that he would return a week later.

On November 11, Weinstein reluctantly informed Ward that arrangements had been made to visit the building, now headquarters of the Soviet company ROSAT, that same day. Inspection of the building revealed some furnishings similar to those of the former embassy, but since they bore no markings, Ward did not press the issue of ownership. Weinstein's assistant, Mr. Orlov-Ermak, led the tour and hurried through the east wing of the building. That displeased Ward because his informants had told him that the old records were on the third floor of that wing. Under the guise of examining a mirror, he reached the stairs to the third floor and later reported:

I walked up the stairway, practically dragging Orlov-Ermak who was assuring me volubly that there was nothing on the third floor but an office similar to [those] . . . we had just visited.

Ward instead found a room lined with cupboards all sealed with wax impressions of the People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs. The lower cupboards had wooden doors, but those on top had glass doors. Scanning them, he saw a volume of the series Foreign Relations of the United States, published by the Department of State. Ward convinced the reluctant Weinstein and Orlov-Ermak to open additional cupboards, where he found many U.S. government publications. All of the books contained the bookplate of the United States embassy. Ward then asked to see the contents of the cupboards with wooden doors. Orlov-Ermak assured him that they contained only ROSAT files but still opened one when Ward insisted. Inside they found bound and unbound files of the former embassy. A search of one of the carriage houses in the courtyard revealed the embassy coat-of-arms above harness hooks and a large pile of volumes that proved to be the embassy's archives dating back to 1807.

A spectacular example ready for further research and display.

Some posts closed in early 1918 because of German military action. When negotiations between the Germans and the Russians at Brest-Litovsk broke down in February 1918, the Germans renewed their assault on Russia. By that time, the Russian army had ceased to function as an effective fighting force, and the Germans advanced rapidly, threatening Petrograd, Moscow, and other cities where the United States had offices.

On February 27, 1918, Ambassador David R. Francis closed the embassy in Petrograd and moved it east to Vologda to avoid the approaching Germans.3 Since he expected a quick return to Petrograd, Francis directed staff to take only records needed for current business. The staff burned the previous 10-year accumulation of sensitive files and left the remaining records in the care of the neutral Norwegians, who assumed responsibility for American interests in Petrograd. One vice consul remained in the city to gather information and to take care of consular business.

In July the Bolsheviks pressured the nine diplomatic missions in Vologda to move to Moscow, which they considered safer. The missions, including the Americans, instead chose to relocate north to Archangel, where they arrived on July 26.5 The Americans took all of their files in Vologda to Archangel.

When the U.S. embassy in Russia closed in September 1919, the staff deposited most of the records it had brought from Petrograd, along with those created in Vologda and Archangel, in the embassy in London. Some files ended up at the American consulate in Vladivostok, too, taken there by staff forced to evacuate to the east. The records earlier left behind in Petrograd were abandoned.